The textbook method for assessing the required investment rate of return for a business is to determine the firm’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). The WACC is an estimate of the average rate of return a company needs to earn to satisfy its investors, and is based on calculating the average cost of both debt and equity used by the firm. The WACC is commonly used to determine the denominator – capitalisation rate – in a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) or Net Present Value (NPV) calculation, essential methods in Business Valuations.

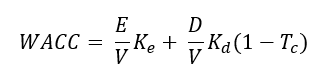

The theory is that a firm typically has a mix of debt and equity to fun its operations and capital requirements. This mix is referred to as the firm’s capital structure. WACC is calculated by multiplying the cost of debt by the proportion of debt in the capital structure, adding it to the cost of equity multiplied by the proportion of equity, and adjusting for the tax benefits of debt, as follows:

Where

- E is the amount of equity in the firm

- D is the amount of debt

- V is the total of E+D

- K is the required yield for the debt (Kd) or equity (Ke)

- Tc is the corporate tax rate, which results in the tax shield (i.e., reduction in tax paid) due to the tax-deductible interest payments.

Note that E/V represents the proportion of equity in the company’s capital structure.

All straight from a Finance 101 textbook.

It is important to note that even in the best of cases, WACC is an estimate. It is not a perfect measure. Like many such models, the devil is in the detail, in this case ensuring you keep in mind the assumptions inherent in its definition. For example, there is an assumption that the capital structure is static, which is rarely the case. WACC can provide useful insight for publicly listed companies and large firms where debt is easily available.

WACC in Small Businesses

In practice, WACC is less suitable for small business valuations.

Many small businesses have uncertain lines between debt and equity, with shareholder accounts acting as a form of overdraft facility and working capital. Many such firms have no real debt, or they have shareholder loans that do not pay (commercial rates of) interest.

Small businesses tend to have a short and inconsistent financial history, making it difficult to estimate realistic debt and equity inputs accurately. Determining the cost of equity and the cost of debt is often meaningless.

Debt is not as readily available to small businesses (certainly not in the way it is to larger enterprises). Financing arrangements are often unusual, even when largely bank-funded. Debt requires personal guarantees and other undertakings that are not easy to price or include in the cost of that debt. Borrowing costs and risk premiums overall are higher when compared to larger, more established companies. Using the standard WACC formula, which assumes a lower cost of capital for larger firms, may result in underestimating the actual cost of capital for small businesses.

Small business owners are more likely to need to rely on alternative sources of funding, such as personal savings, loans from family and friends, or small-scale lenders. These financing options may have different interest rates and terms than traditional debt and equity sources, which can impact the WACC calculation.

A small business’s capital structure tends to be far less stable and predictable than a larger business. The dynamic nature of capital structure makes it challenging to apply a static WACC calculation.

WACC assumes that a company’s risk is diversified across different projects and business segments. However, small businesses often have a narrower focus and may be more exposed to specific risks. This lack of diversification makes it difficult to apply the WACC formula accurately or meaningfully.

The application of WACC involves estimating the beta coefficient of the firm, which measures a company’s sensitivity to market movements. Determining a beta for a small firm is meaningless, making it impractical to determine the cost of equity. Their stock isn’t traded, and is typically highly illiquid.

Small businesses need to use alternative methods for determining their cost of capital. We typically use (and recommend) a built up cost of capital based on the component factors of risk. This approach will be discussed in a later article.